On the 22nd of June 2021 a post appeared on RaidForums titled “New LinkedIn 2021 – 700Million records”. The author’s post contained an advert for the sale of “700 Mlilion” 2021 LinkedIn Records [a now Microsoft owned company]. The advert offered a 1 million record sample file.

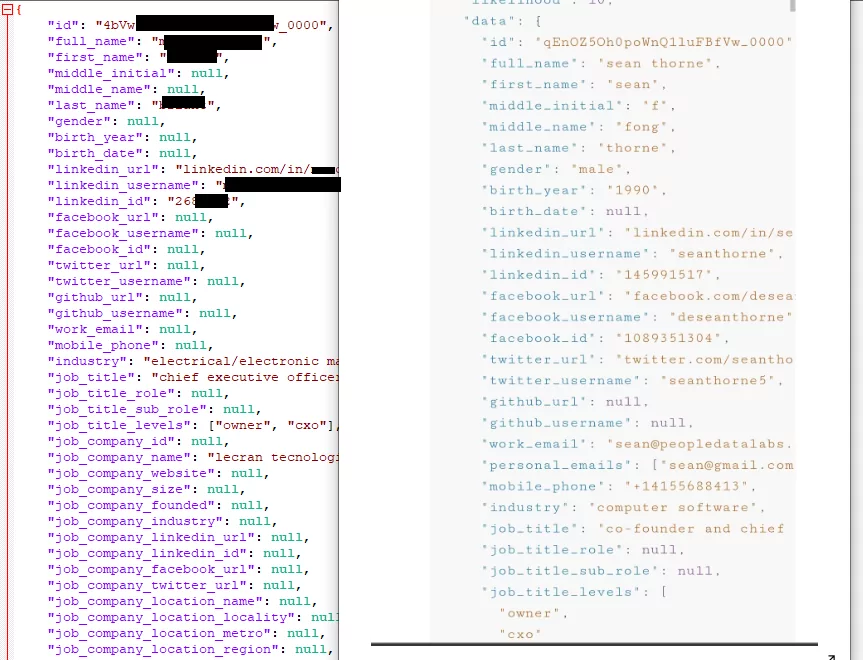

This sample file consisted of rows of JSON formatted data suggesting the origin of the data was an API.

There have been many discussions and outright arguments around this specific data breach – arguing for and against this being a “scrape” and not a breach. With some very high profile people going on record stating this is a data scrape and not a breach (Troy Hunt, a Microsoft MVP and Regional Director).

What we have not seen is anyone looking into the data set itself and trying to identify the likely origin of it.

Initial Analysis

Our analysis started by reviewing what available fields that contained data in this data set. What became clear quite was that this data set contained items that one would not expect to be on a public profile. Items such as geographic data points, personal email addresses, “inferred” salary etc.

Analysis continued with a cross reference sample of profiles showing that:

- the data in this sample was real and relates to actual current profiles

- the data set contains items in information not found to be publicly shared, for example: personal email address, phone number etc.

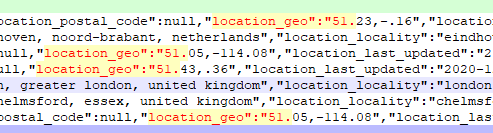

In most cases when a geographic data point was available in the “location_geo” field it contained longitude and latitude to what could very likely be the actual location of that individual and or their workplace.

It is now clear that this data set is not a data scrape of only publicly available data. It is much less likely that this is a scrape and “hacker” enriched data due to the cleanness and data-model consistency. How do we know this? Looking at a comparison of other “hacker” collated data sets seen before.

Sticking with the evidence

There are clear indications that this is not a public data scrape and not a mass data aggregation by the individual selling the data.

We need to identify where these “inferred” fields are coming from and who is inferring them.

- Is it LinkedIn?

- Is it the hacker?

- Is it some other service?

The smoking gun

Addressing the topic of fields and origin. It is becoming clearer at this point in the investigation that we are dealing with real data.

Some of it is not public and it is all structured in a standardised, clean and you could say professional way.

Where did this data come from and it did it come from Linkedin?

Assuming this is data derived from an API there are a few interesting fields we can look at to match against known API samples. The first being the “id” field, then formatting of the general field names and then the “version_status”, “pervious_version”, “current_version”.

The id.

Looking at OSINT around the official LinkedIn Profile API we see that LinkedIn does set an id field, yet the format of this field is of a numerical value, for example “1234567890”. This doesn’t fit in with the id’s we see in our dataset, that have an alpha numeric formatting with “-” and “_” separation.

For example “4aBw-2LKiqQs0xfvflaXf9W_0000”.

Each id we see in the sample always ends in a _0000.

This is completely unlike the LinkedIn id data, and further in this data set we actually see a “linkedin_id” field name with values that match LinkedIn’s own API id field number format.

So by this we can infer that this id field is part of a different data model, that the data model source is unlikely to LinkedIn and the entries contain as a reference, “linkedin_id”.

Field name format

A minor point but an important one. Within the LinkedIn API samples we found their field names with a “-” whereas in this sample the field names are all separated with a “_” . Suggesting further that this data model is not consistent with LinkedIn’s own API standards.

The source

Where has this data come from ? We can be sure that it wasn’t directly from a Linkedin API.

Continuing with the use of OSINT techniques we were able to identify matches against some of the non-generic field names back to a service called People Data Labs.

The most significant piece of evidence to suggest that People Data Labs are the source of this is the ability to tie that “id” field back to the “PDL” id format.

The id format is identical to the ones “PDL” supply in their API documentation samples, further the field name formatting is separated by underscores and the fields match that of our sample, containing inferred salary, inferred time at a job and location_geo references. Now with a high degree of confidence, supported by PDL’s own API samples are we able to say that the “LinkedIn 700Million 2021” data dump doesn’t directly come from LinkedIn or as was suggested an abuse or hack of LinkedIn’s APIs, but rather an data enrichment and aggregation service provided, commercially by People Data Labs.

Breach or not a Breach?

The key question around this data set is could all this data have been scraped from publicly available sources and if so, does personal data in the public domain justify it not being a data breach?

I think we can safely answer no to both of these points.

As we have demonstrated the data set contains overwhelmingly large amount of LinkedIn specific data, data that may have been enriched and “inferred” by PDL based on LinkedIn profiles but the most important factor here is that this data set contains non-public data.

Restricted Fields

One of the most important factors here is the evidence of fields and values contained in this dataset and by PDL’s own documentation on “personal data” are Restricted Fields[https://docs.peopledatalabs.com/docs/restricted-fields].

Access to Restricted Fields is as per People Data Lab’s own website possible only after talking to a data consultant – presumably after payment to a commercial plan and some due diligence done on PDLs part.

The fields observed in the data set, for example languages, experience, certifications and most importantly here ” linkedin_connections” appears to be, as described by PDL’s documentation, an integer “number of LinkedIn connections”.

A value obtained via the LinkedIn API alongside the other some publicly sharable and non-publicly sharable attributes suggests very strongly that this data came from a customer of PDL who has paid for access and with PDL’s own integration with LinkedIn’s API has been able to extract data that is “restricted”.

This could be as a result of a compromised PDL customer, or granting of access to PDL following lack of or poor due diligence, or the unauthorised access to PDL’s API. How this occurred is yet to be determined and likely by someone else other than us.

What we can conclude on is that:

- Yes – this was a breach

- No, this wasn’t a direct hack of a LinkedIn API

- The dataset appears to have been enriched by PDL

- The dataset originated from PDL & contains restricted non-public fields

The other unanswered questions remain.

Does the total data set being sold actually contain 700 Million profiles as claimed?

Now that we know this isn’t direct LinkedIn data this may put these claims to doubt.

If the total data set does actually contain that much data – how did the collection of so many profiles from PDL not trigger any alarms ?

The most valuable thing we can draw from all of this is the importance of basing a decision or opinion on the facts at hand.

A number of high profile individuals called this out as a non-breach, “just a scrape”.

This was on the assumed basis that this data set was an old aggregation of publicly scraped data and in no way challenging Linkedin’s position.

All it took was a dive into the sample data set and a bit of OSINT work leading to a much more evidence-based conclusion.