Held annually on 28 January every year since 2007, Data Privacy Day was introduced by the Council of Europe to commemorate Convention 108 – the first, legally binding, international treaty on data protection signed in 1981. Data Privacy Day exists now to bring the concept of data privacy to the forefront, and encourage everyone to consider the steps they take to keep their data safe, and what more they could be doing.

The landscape of data privacy has changed dramatically since that first celebration in 2007. Wholesale changes to legislation have been implemented, new international regulations brought in and enforced, and on the whole, a shift in the dynamic of how the general public thinks about the privacy of their data.

Managing your data privacy can be a daunting task – our data is everywhere, and we’re not always consciously aware of what is happening to it. Unsecured data, oversharing online, interacting with suspicious communications – these are all things that the threat actors of the world rely on from their victims to achieve their criminal goals. Here are several simple things that can be done to improve your online privacy:

- Limit sharing on social media

Social media is a gold mine of information for those with malicious intentions. Sharing events such as birthdays, names of loved ones, employment details etc, can allow a threat actor to very quickly socially engineer scams to encourage you to divulge sensitive information. Although we shouldn’t, quite often those details such as birthdays and loved ones’ names end up in our passwords too, so it doesn’t take much for a threat actor with a little motivation to work these out. Ensuring privacy settings are set to maximum, and not over-sharing, will do much to protect from these threats.

- Think before you click

We receive a deluge of emails every day, in both our personal and work lives. Threat actors know this too which is why they’ll use email as a method to target individuals and businesses to gain access to sensitive data. Phishing scams rely on the innocent victim not realising that the email in front of them is fake, or trying to get them to do something they shouldn’t be doing. So if in doubt, stop and think before clicking on links or opening attachments.

- Know your rights

Know your data privacy rights, and what applies in your country. In Europe, this will be GDPR, which gives a lot of control back to the person to whom the data relates. This includes:

- The right to be informed

- The right of access

- The right of rectification

- The right to erasure

- The right to restrict processing

- The right to data portability

- The right to object

- Rights in relation to automated decision making, including profiling

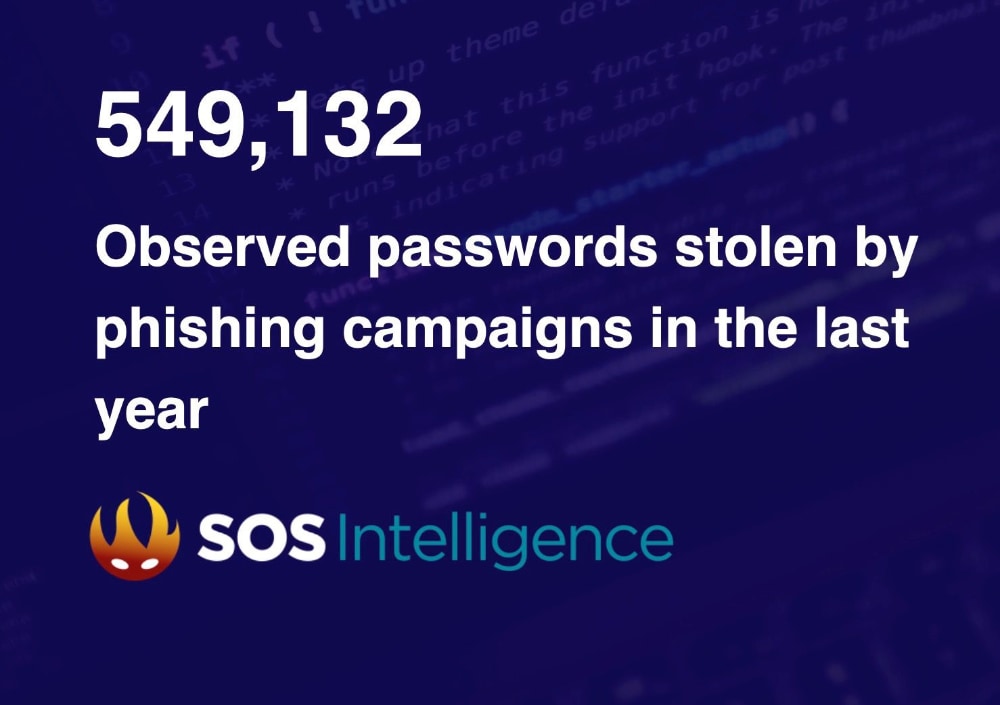

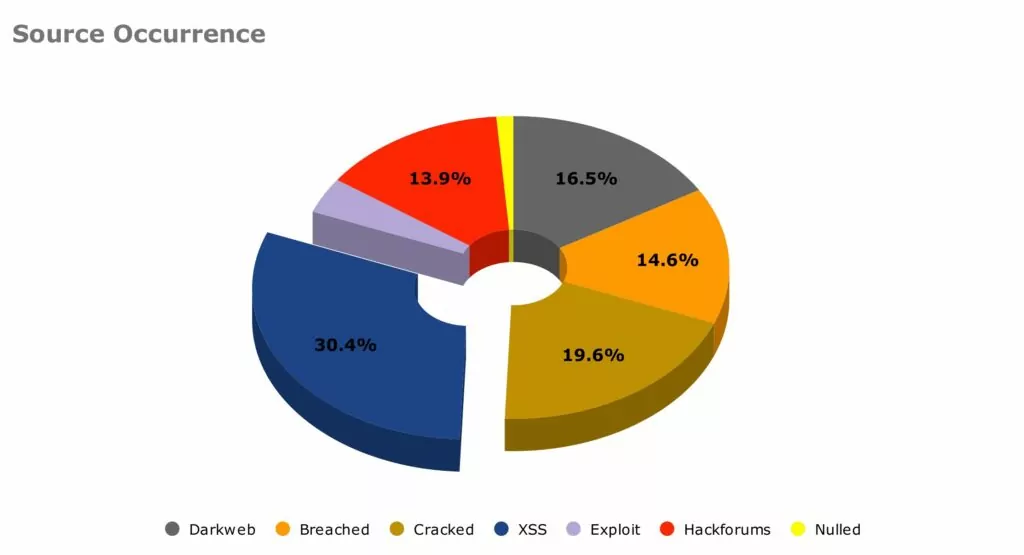

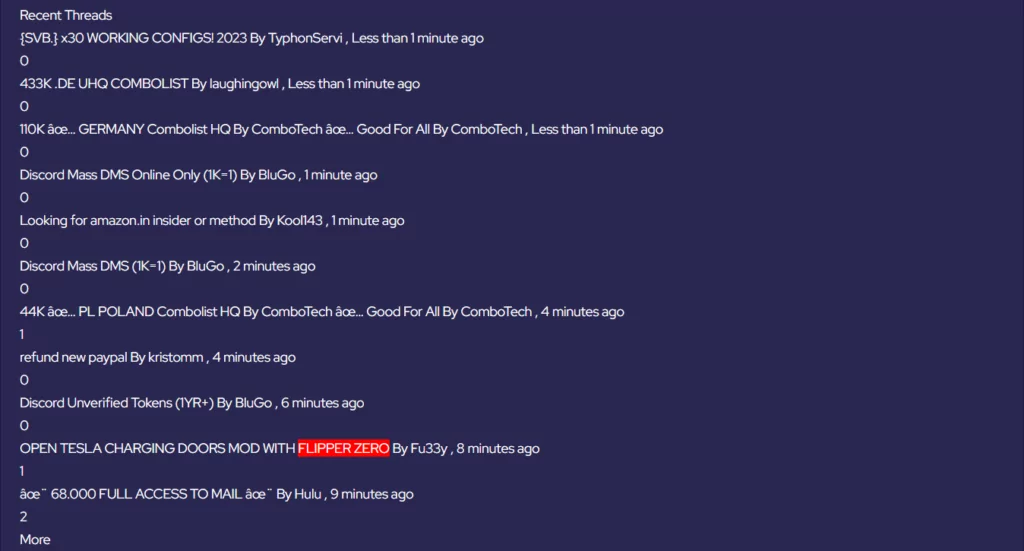

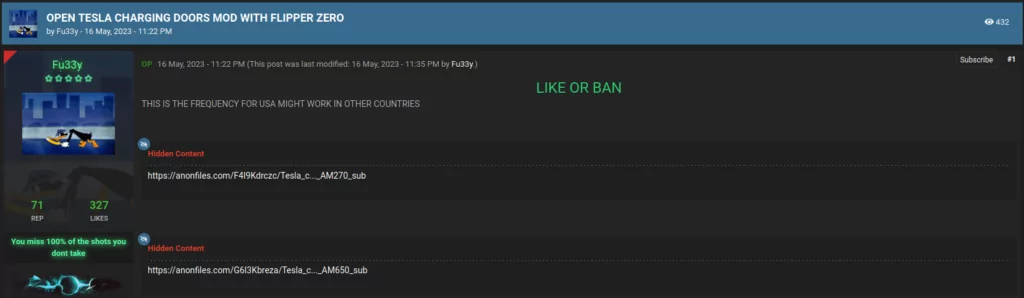

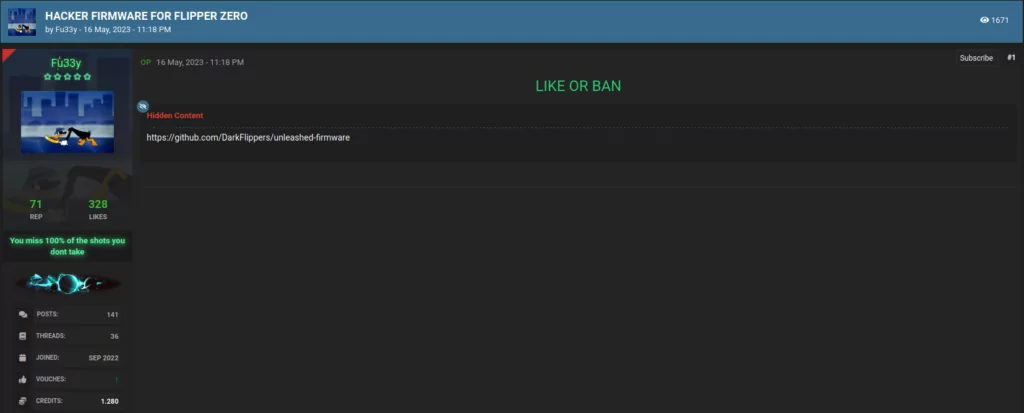

Despite best efforts, threat actors are constantly looking for new and novel ways to gain access to our data, and inevitably, some of this will be stolen and used for criminal activity. SOS Intelligence has been diligently monitoring the digital landscape over 2023. Our recent findings are a stark reminder of the rising threat of phishing attacks. Over the past year, we have observed over half a million unique credentials compromised through phishing, and with the growth of Generative AI techniques, we expect that number to grow in 2024.

One standout feature of our technology is our real-time alert system. This capability ensures that our clients are promptly notified when their staff have fallen victim to phishing, allowing for a swift response and effective risk mitigation, helping you to ensure that your data remains as private as possible.

Photo by Jason Dent on Unsplash

Recent Comments