How threat actors target your credentials and what you can do to protect yourself

Across the dark web, and shadier parts of the clear web, there is a booming marketplace for compromised credentials. Threat actors are looking to make a quick return can monetise your sensitive data, leaving you vulnerable to further compromise. So how do threat actors get ahold of your credentials, and what can you do to protect yourself?

How do threat actors get your credentials?

Threat actors have an arsenal of tools and techniques for obtaining credentials to facilitate further criminal activity. These range from the highly technical to meticulously researched to plain and simple brute force. We discuss a sample of these techniques below to assist you in understanding how threat actors can obtain your credentials.

Malware

For the more technically-minded, malware can be utilised to intercept passwords being input across the internet, or just simply to steal passwords from your device.

A “man-in-the-middle” attack sees a threat actor tactically position themself between a victim and the service the victim is accessing. While the victim is inputting their credentials, the threat actor can see the input and capture this for their use. This technique has commonly been utilised with banking trojan’s, such as TrickBot.

Once installed on a victim’s device, TrickBot would identify when victims attempted to access banking services online and provide them with a cloned website, controlled by the threat actor. Subsequently, they would then be able to see what the victim was typing, thereby gaining access to their login details. To preserve the illusion that nothing was amiss, the threat actor would then redirect the victim to the legitimate site as if they were logged in. The threat actor would then capture the victim’s credentials, allowing them to log in whenever they saw fit.

Infostealer malware is much simpler. Once installed on a device, it can quickly query common areas of a device used for password storage, and send this data to a waiting server controlled by a threat actor. Owing to the various deployment methods used, threat actors can quickly generate a large volume of content from infostealer malware. This content is then sorted and sold online, or at times even given away. Further information regarding infostealer malware can be found in our article here.

Phishing

Phishing requires an element of trickery from the threat actor. In this situation, they are portraying themselves as something they aren’t to trick the victim into divulging their credentials. This can often be in the form of messages (email, SMS etc) asking victims to clarify their credentials associated to a legitimate service, i.e. banking, or premium services such as Netflix. The threat actor will also provide a convenient link for the victim however, this link will invariably lead to a cloned website controlled by the threat actor, who can then collect credentials as victims input them.

Social Engineering

Remembering passwords for all the different services we use can be tiresome. It has been estimated that the average person has over 100 passwords to remember. Therefore it’s only natural that we utilise the things in our lives that matter most when coming up with passwords. Significant dates, names of pets, and our favourite locations. All can be useful when creating passwords as you’re more likely to remember these details.

The problem comes with our online activity. Many people are very public about what they post online, and we talk about the things we like and what’s important to us. If we’re then using those important things to generate our passwords, it becomes very easy for threat actors to do a little research into us to discover those passwords for themselves.

As an example, we have identified within our data collections that “fiona2014” is one of the most commonly used passwords. If someone were to be using this password, it could be very easy to use social engineering to obtain it. It would be straightforward to talk to someone, engage them about their life, and quickly find out they have a daughter called Fiona who is 10 years old. Putting these details together we can come to “fiona2014”.

Dictionary Attacks

We are inundated with accounts requiring passwords, so it is common for people to use simple passwords to avoid having to remember anything too complex. Threat actors rely on this as the basis for a “dictionary attack”. Years of data regarding passwords has allowed for generating files containing thousands of common passwords and their variants. These files then allow a threat actor to query a service, armed with a victim’s email address, and try each password until the service allows them to log in.

Thankfully, dictionary attacks are somewhat easier to defend against. Most services will now only allow a few login attempts before any suspicious activity is flagged and the account is locked down. Threat actors will constantly look for methods to bypass this security, so the best option is to keep those passwords unique.

Brute Force

When finesse will not work, take a sledgehammer to the door. Brute force requires a threat actor to have some coding knowledge. They can write code which will query a service to attempt a login, but instead of being more methodical, this method is more trial and error. Commonly, brute force attacks will iterate through millions of potential combinations to find the correct password (assuming that any security the service has does not lock the account down). This method can be more easily defeated by using longer, more complex passwords, and we will explain why shortly.

Brute force attacks can also occur when a threat actor obtains a username:password combination for a particular site. Banking on poor password hygiene, they will attempt the same combination across multiple sites to see if there has been any password reuse.

What happens when your credentials are compromised

What happens when credentials are compromised depends on who the victim is.

Compromise of personal accounts tends to provide threat actors with access to various services and information, including the victims’ banking, online shopping, premium entertainment services etc. These have some value to others, who may want the benefits of those services without having to pay, e.g. to watch Netflix, listen to Spotify etc. These types of data will often be grouped and sold in bulk on online forums for a fraction of the cost of the service they give access to.

Real value for threat actors comes from compromised corporate accounts. These accounts allow a threat actor to access a corporate system, giving them a platform to launch further criminal activity. There is an entire marketplace dedicated to gaining initial access to corporate systems – initial access brokerage – and depending on the size of the victim, can bring in thousands of pounds for the threat actor selling credentials. Such access can be a precursor to more serious cybersecurity events, such as data theft/loss, or the deployment of ransomware.

Password hygiene and habits

Now for the statistics.

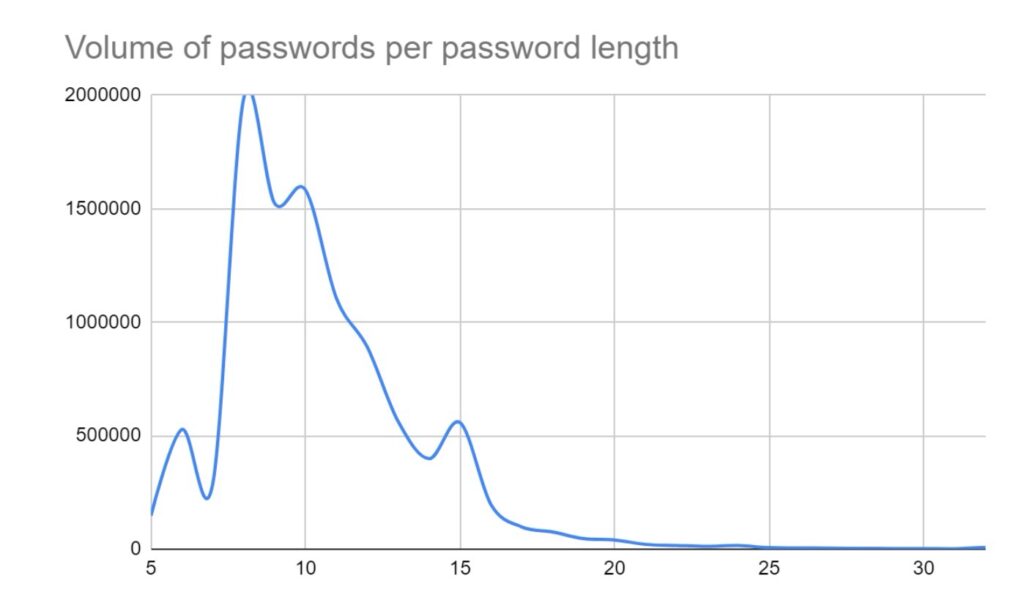

We have taken a sample of data collated by SOS intelligence in March 2024, totalling over 10 million passwords obtained by infostealer malware.

The most common password length was 8 characters, with an average length across the dataset of 10.5. This was to be expected as 8 characters is often presented as a minimum across many password policies. Additionally, it’s also the number of characters in “password”…

| Top 20 most common passwords | |

| Password | Count |

| 123456 | 51022 |

| admin | 22322 |

| https | 16682 |

| 12345678 | 16525 |

| 123456789 | 15737 |

| 12345 | 8958 |

| Profiles | 8611 |

| password | 6533 |

| Opera | 3946 |

| 1234567890 | 3326 |

| 123123 | 3093 |

| 1234567 | 2923 |

| Aa123456 | 2866 |

| Kubiak22 | 2821 |

| Pass@123 | 2761 |

| Password | 2665 |

| 111111 | 2488 |

| fiona2014 | 2206 |

| 12345678910 | 2043 |

| P@ssw0rd | 2029 |

On that note, the word “password”, and numerous variants utilising common character substitutions, appeared over 37,000 times. “admin” appeared more than 22,000 times, while “https” was used more than 16,000 times. This is concerning as dictionary attacks will often focus on keywords such as this first, knowing they are so common. “admin” is frequently used as a default password on routers and other IoT devices which highlights the ongoing vulnerability of these devices.

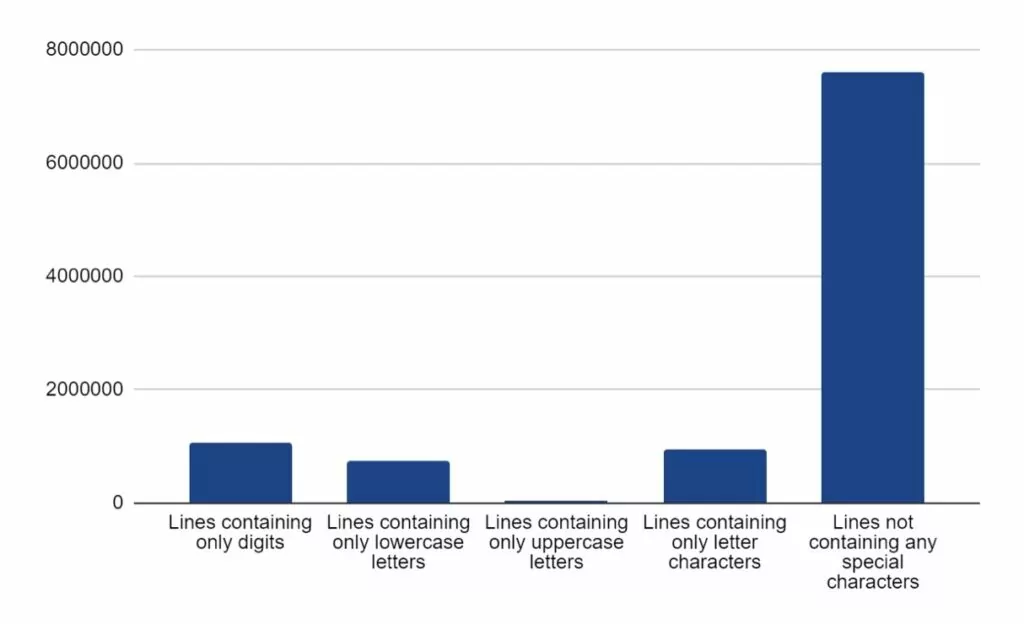

In total, approximately 1 million passwords contained only digits, while approximately another 1 million contained only letter characters. Overall, over 7.5 million passwords contained no special characters.

So the fundamental question is, why are these statistics important, and how can we use them to improve our password hygiene?

Password strength works based on “entropy” – the measure of randomness or uncertainty of the password. Password entropy allows us to quantify the difficulty or effort required to guess, or “crack”, a password using brute force or other similar methods. As a general rule, higher entropy passwords are deemed stronger and more secure.

We measure entropy in bits. The number of bits a password has indicates how strong it is. The basic formula for calculating entropy looks like this:

Entropy = log2(NL)

Where:

- N is the number of possible characters in the character set used for the password

- L is the length of the password (in characters)

- log2 is the base-2 logarithm

Taking this formula we can see that the longer a password is, and the more characters it pools from, the higher entropy it will have. We can visualise this with our data.

Using a length of 8 (being the most commonly seen) we can see the entropy when different sizes of character sets are used:

| Numerical | Single Case | All Case | Alphanumeric | Alphanumeric w/ Special Characters | |

| Total # of characters | 10 | 26 | 52 | 62 | 92 |

| Entropy | 26.58 | 37.60 | 45.60 | 47.63 | 52.19 |

If we increase the password length to 12, strength increases significantly:

| Numerical | Single Case | All Case | Alphanumeric | Alphanumeric w/ Special Characters | |

| Total # of characters | 10 | 26 | 52 | 62 | 92 |

| Entropy | 39.86 | 56.41 | 68.41 | 71.45 | 78.28 |

Based on the above, working at 1000 guesses per second, a brute force attack on an 8-character numerical password would take about 27 hours. However, a similar attack on a 12-character password utilising alphanumeric and special characters would take roughly 11.5 billion years!

The key factor to note here is that there is a reason we’re always asked for longer passwords with uppercase, lowercase, numbers and special characters – they’re that much stronger and secure.

So a crucial question remains; what should be done with this information? We sincerely hope that what we’ve discussed here will highlight the need for strong and enforced password policies. These should factor in the following:

- Use of alphanumeric and special characters

- Mandatory lengths (at least 10, but longer is better)

- No password reuse

- Frequent and enforced password changing.

Wherever possible, we would highly recommend the use of password managers. They can save a lot of time for users, allow for significantly more complex passwords to be used, and only require the user to remember one password. We don’t recommend using one product over another, but one such example would be KeePassXC. KeePassXC is a host-based password vault which keeps passwords encrypted when not in use. It offers numerous options for password generation, varying on characters used, length etc. The benefits of this are that you can generate passwords up to 128 characters long, which simply need to be copied and pasted whenever they are required. Here is one such example with an entropy value of 715:

J4kKutHec3RYxQo3kpm4mot5EAVp&opRCSr&x4J5r%fQ$XxzrjdW2ZgRg@k42XhA@zz`S4ofiR4~^s`&43zZ@JQ&qQ$Mad2^jtQdHSZ@hbJbVk5Qabvs5Kc$KW3#W@Rm

What our external research shows

Research conducted by NordPass in 2022 identified that the average person has approximately 100 user accounts requiring password verification. This is the most probable cause for password reuse and password fatigue; where users are exasperated by the constant need to generate unique strong passwords and fall into a habit of using weak, easy-to-remember passwords, or reusing old ones. Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report, published in 2021, estimates that 80% of hacking-related breaches were a result of stolen or brute-forced credentials. This number could be significantly reduced by ensuring and maintaining good password hygiene.

Forgetting passwords can have a significant impact on the password owner, the services they use, and the organisations they work for:

- Research firm Forrester has indicated that, for some organisations, the costs associated with handling password resets could be up to $1 million USD per year. Gartner estimates that around 40% of help desk queries in large companies relate to password resets, taking up a substantial part of billable work, and taking focus away from more business-critical support.

- In 2017, MasterCard and the University of Oxford published a study looking at users of online shopping platforms. Their research indicates that 33% of users would abandon a purchase if they could not remember an account password, while 19% would abandon a purchase while waiting for a password reset link.

- Chainalysis, a cryptocurrency data firm, estimates that 20% of all mined Bitcoin are locked in lost or otherwise inaccessible wallets. In one such example, one user has 7002 Bitcoins locked within a hard drive, which risks being encrypted following two more incorrect password attempts.

What is SOS Intelligence doing, and how can it benefit you?

At SOS Intelligence, we understand the risk that credential theft can pose to the security of your data. What we can provide is early detection for when your data has been exposed.

We are actively collecting and analysing stolen credentials from multiple sources which feeds into our intelligence pipeline. Within moments of ingestion, we can generate bespoke alerts for you to indicate when you may be at risk. Early detection is vital to allow you to take action before an issue becomes serious and impactful against your business.

If you are serious about your cyber security, why not book a demo?

Photos by Ed Hardie on Unsplash, Ryunosuke Kikuno on Unsplash, Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash